Building the mki x es.EDU analog synthesizer

[music electronics analog synth Seeing a Suzanne Ciani performance at Ambient.Church inspired me to get into analog synthesizers. To learn more about the electronics aspects, I built the mki x es.EDU analog synthesizer kit Some notes, recommendations, and reflections on the process…

What I especially liked about the system

It was not my first kit in this process. I started by buying Ray Wilson’s Make:Analog Synthesizers book, acquiring a PCB and parts kit from Tindie, and 3d-printing an enclosure. I do not recommend this route. I never got the kit to work (the part tolerances were out of spec, but maybe I also did a bad soldering job?). The circuit is not laid out in a way that is easy to debug, and one ends up making a rats nest to the surface controls. There isn’t really a comprehensive theory section in the book (although in retrospect I could fill that in now, but not when I was just starting.).

What I really wanted was to learn the theory (at least qualitatively) of analog design and to build small, easily testable submodules. The mki x es.EDU kit does this well. The manuals are available online and convinced me that this would be an educational project, rather than merely an exercise in soldering and knob twisting. There are also youtube videos that describe the theory (essentially just repeating what is in the PDF manuals) if you are into that type of thing. I would sometimes watch the videos while drinking a martini, but generally preferred reading. Some third parties have also made build-along videos, which are linked from the Ericasynth.lv website.

FWIW, I ordered mine from Thonk.uk, taking advantage of the favorable exchange rate and free shipping and it arrived promptly in the US; it was a few bucks cheaper than ordering direct from Ericasynth.lv.

Recommendation: Buy an oscilloscope and some convenience adapters

If you’ve done any electronics you will likely already have a multimeter; if not, get one!

I’ve held out on buying an oscilloscope until now, but it was worthwhile to look at things without having to go to the lab. I ended up buying a Zeeweii DSO2512G (dual probe) scope off AliExpress based on a good review of its single-channel cousin It’s a nice little gadget, and I have no complaints.

It is also useful to buy some convenience adapters for attaching multimeters and oscilloscopes to the analog system. I am pleased with the BNC male to 3.5mm audio male and 3.5mm audio male to alligator clip adapters. The seller was even nice enough to combine shipping and give me a small refund.

Where to get spare parts

While breadboarding the envelope generator I short-circuited a potentiometer resulting in acrid blue smoke and a broken potentiometer. (I also suspected that I had damaged an op-amp by shorting it, but then did some breadboard tests to convince myself it was OK).

The kit uses tall Song Huei potentiometers, available (in the USA) from Antique Electronic Supply

Suggested order of building the modules

General advice: Clean your flux—some fluxes can give you high resistance conductance paths which will screw with the circut. Also it looks messy. I use high proof isopropanol from the local drugstore and an old toothbrush. My favorite solder is sparkfun lead free, which in theory has a water soluble flux, but I use isopropanol anyway, at about 330C.

- Power supply and case: you need a power source to drive the other modules. There is no theory here, but you’ll get to practice your soldering. The instructions don’t say this, but the LEDs follow the standard polarity convention: long leads go into the square pad holes (same for the electrolytic capacitors). This is described in subsequent manuals, but not in the power supply manual. In the worst case, the LEDs won’t light, but there’s not enough current flowing to blow them out, so if you get it wrong you can just desolder the LEDs and turn them around. (How do you think I know this…?) Possible gripes: (i) There are pads for adding +/-5V output support, but this is not built out (the other kits only use +/-12 V output. ) (ii) There are 14 outputs that this gives, but only 10 are used in the kit…but the case does not provide an easy way to get these out. It would have been nice to just make the case bigger and provide some dummy panels to cover the void….or to be filled in by other modules that get designed. Or at least some passthrough in the case to get the power cables out. (iii) It’s not strictly a “eurorack” case, as the are pre-drilled holes that only allow these modules to be mounted in a specific order.

- Voltage controlled oscillator (VCO): an oscillator is the core of an analog synth, and this is a very good starting place to learn about the key elements of op-amp behavior and general design philosophy used throughout the process. It’s a Schmidt-inverter based triangle wave, that gets converted to a square wave. Once you build this you can generate pure tones—just connect the output to your headphones or stereo and you’ll be good to go. FWIW, with the trimmer pot and the coarse and fine pots dialed down as low as they’ll go and no inputs, I can get to about 8.4 Hz (C0 should be 16.35 Hz). But then I end up chasing this without getting an even multiple while tuning…

- Sequencer The basic idea is to use a decade counter to select which voltage-divider signal to pass through to the output. There is a lot of repetition, but the core ideas are simple: decade count IC, use potentiometer as a voltage splitter (to control the input voltage), do some isolating, and generate a clock to march the decade counter. All great concepts to learn. Once you build this, you can use it to drive your VCO and make some tunes.

- Envelope generator (EG) You’ll eventually build two of these, but one is enough to get started. Great practice/review of RC circuits. You can drive this with your sequencer and do some whimsical things, or run it on loop. Potential gotcha: you might think that the external gate doesn’t work if the attack and decay settings are too low or high. Fiddle with those first before you think there’s a bug in your circuit. Potential modifications: With the default value of R9 = 47 k, you need a 4.1V gate to trigger the circuit. Not all sequencers can do this (if they are 3.3 V devices, for example…). So you might consider replacing R9 = 22 k Ohm, which reduces the trigger threshold to 2.4 V.

- Mixer It’s nice to have a quick win: the theory is straightforward, the soldering is easy, and it is satisfying to see the combined outputs on an oscilloscope. Feel free to put this earlier if you need a quick win to boost your motivation.

- Wavefolder Another quick-win module; relatively short and quick to build. Especially satifying to see the folding on an oscilloscope during the build process and drives home the idea of “centering” the AC signal with a capacitor.

- Voltage controlled amplifier (VCA) Differential amplifier! If you take a closer look at the schematics, you’ll see that the nominal behavior is for the IN1 signal to appear on OUT2 if there is nothing connected to IN2 (becaue of the way the plug is “normalled”), but a signal from IN2 will under no circumstance appear on OUT1. This is a feature, not a bug: It lets you put a single signal into IN1 and then do separate modifications based on CV1 and CV2 resulting in separate outputs. But it can cause confusion when you are trying to figure out if your circuit works.

- Voltage controlled filter (VCF) This is another long project, but very fascinating to think about RC circuits as filters. Don’t assume that your circuit is broken if you don’t hear anything: A low freqeuncy input will just be entirely filtered out, so be sure to change both your VCO input and your cutoff before concluding that you did something wrong (this applies especially during the breadboard stage).

- Noise/Sample-and-hold Long project but interesting. Generating noise with transistors is a fascinating topic. As an aside, in principle you could generate any sound by starting with white noise (which contains all frequencies equally) and applying the appropriate filters.

- Output/stero mixer The manual for this one is written by an electrical engineering prof. It was far more technical than the others and kind of went over my head. Constructing the circuit is straightforward, although some versions of the PCB indicate DNM instead of the 1k values for two of the resistors But the photos in the manual do clearly indicate these should be 1k.

- Go back and complete that last EG.

Calibration and tuning

Several modules require calibration or tuning by adjusting a trimpot or two. An oscilloscope will help, but there are also ways you can do it by ear.

- VCO calibration seeks to make a 1V/octave response. You’ll need a voltage source to do this; if you don’t already have a sequencer, it will be hard. My original thought was that I would use the sequencer to do this…but you really want something slower than that. So I used an EG as an external clock. Use a multimeter to the CV to fine tune the values. I ended up minimizing the mean square error based on 0, 1, and 2V inputs (which should result in a base frequency, 2x that frequency and 4x the base frequency). Satisfyingly, it is pretty close to setting C0 at 16.3 Hz. See appendix below. Another possible approach is to use a USB as a 5V source, and then construct a voltage ladder with 1k 1% resistors and listen for even octaves.

- Sequencer calibration requires tuning trimpots to achieve a maximum of 2.5V and 5.0 V output. Tolerances of the resistors sometimes makes the latter infeasible, and a way to fix this is to add an additional resistor in series. Or just live with it, because it is analog…you lose a bit of the end of the range (but if you’re old you can’t hear those high frequencies anyway, ha ha) and it doesn’t modify the tuning.

- Mixer trimpot modifies the amount of clipping for the CLIP OUT. The process is described on pp. 16-18 of the manual. It’s just an aesthetic choice—adjusting the trimpot results in more or less clipping, so if you don’t like the level you can fiddle with it. Otherwise there is no “right” value.

- VCA You’ll need to eliminate the transistor mismatch (pp.27-28) by hooking up the output to an oscilloscope and adjusting the trimpot until the waveforms mid axis is aligned with zero volts. (You can calibrate this by ear without an oscilloscope if you are so inclined. I did it with an oscilloscope, but given how the duty cycle and voltage offsets of the VCO vary with frequency (and how the offsets vary with those, for reasons described here), I think doing it by ear would give you about the same result).

- Wavefolder You are supposed to make the gap between the rising slope and the falling slope to disappear. Put the saw wave output from the VCO into the SAW-TRI input and dial down the intensity. It should look like a triangle wave. Adjust the trimmer pot until you get it to be as “sharp” a triangle as possible. You can try a few different frequencies. It may be easier to route the saw wave through a mixer and use that to reduce the input signal strength—you’ll see the discontinuities more clearly on your oscilloscope at lower input swings.

- VCF Adjusting the trimmer modifies the resonance response (p.40) If you are getting some resonance response then you are OK. Adjusting this changes the base gain, and “the more base gain we dial in, the more the diodes in the feedback path are going to be activated. When you push this past a certain threshold, those diodes are going to start warping the feedback in strange ways, resulting in a much more gritty-sounding resonance.” But essentially this is just an aesthetic effect rather than anything with a precise calibration goal.

Modwiggler/twitter posts along the way

- Question and answer on output/stereo mixer module

- Comment on sequencer tolerances

- Comment on VCA behavior

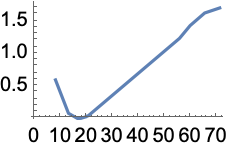

Appendix: Tuning the VCO by mean square error loss

mse[{v0_, v1_, v2_}] := {v0, ((v1/v0 - 2)^2 + (v2/v0 - 4)^2)}

obs = {

{7.9, 16.9, 37.6}, (*clockwise most*)

{12.9, 26.5, 55.2}, (*somewhere in the middle*)

{16.4, 32.7, 66.08}, (*fine tune int he middle, and tune to middle C at zero CV*)

{59.8, 101, 170}, (*still room to go more to the right*)

{71.2, 118, 195}, (*too far...loss function goes up*)

{65.4, 109, 181},

{55.7, 95.1, 163},

{19.8, 38.6, 76.0},

{20.6, 40.0, 78.2},

{20.3, 39.4, 77.3},

{20.0, 38.9, 76.3},

{18.7, 36.5, 72.6},

{17.7, 34.9, 69.9},

{17.1, 33.7, 67.7},

{16.7, 33.2, 66.9}

};

mse /@ obs

ListLinePlot@Sort[%]

(*{ {7.9, 0.596219}, {12.9, 0.0808245}, {16.4, 0.000893813}, {59.8, 1.43583}, {71.2, 1.70816}, {65.4, 1.62996}, {55.7, 1.23827}, {19.8, 0.0286705}, {20.6, 0.0449618}, {20.3, 0.0404038}, {20., 0.03725}, {18.7, 0.0161572}, {17.7, 0.00338345}, {17.1, 0.00253069}, {16.7, 0.000179282}}*)

Appendix: Ideas for future hacks

- The power supply system uses a wall-wart to provide +12VDC @ 1 A as input to the bipolar converter. In principle you can replace the wall-wart with USB-C by using a HUB238 USB power supply chip (which will readily supply 2-3A if you wish).

Appendix: Parts and supplies

- Elecric Druid source for analog ICs for VCOs, VCAs, delays, LFOs, etc.

Appendix: Drum modules

(22 Mar 2025) Subsequently, they released an analog drum kit, which includes a kick, snare, hi-hat, an additional mixer, and a compressor.

The base kit, described above, has enough power for this, but not enough space, so this lead me to a side-quest of building a new rack

I found the kick and hi-hat to be interesting (and suggest building them in that order). The snare is rather repetitive, as it builds on a lot of the other ideas, and the breadboarding is super dense. To be honest, I got bored with the snare, and would probably suggest skipping it. (Still working on the compressor…)

The main limitation is that mki x ES sequencer doesn’t support making interesting beats (not even ye-old 4-on-the-floor techno). So you need a fancier setup to make something musical.